The chapter defines research specialty as a self-organizing network of researchers that tends to study the same research topics, attend the same conferences, publish in the same journals, and also read and cite each others’ research papers.

Other definitions of research specialties:

- Kuhn (1970) - communities of one hundred members, sometimes less

- Price (1986) - an “invisible college” of approximately 100 “core” scientists, monitoring the work of individuals who are rivals and peers by reading about 100 papers for every one published

- Lievrouw (1990) - a set of informal communication relations among scholars or researchers who share a specific common interest or goal

- Small (1980) - consensual structure of concepts in a field, employed through its citation and co-citation network

- Rogers, Dearing, and Bregman (1993) - a family tree in which earlier studies influence later studies

|

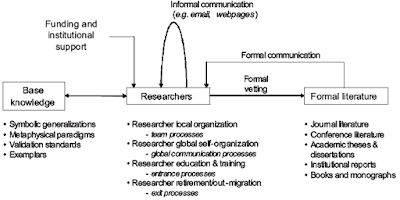

| Fig. 6.2 from "Mapping research specialties" |

Studies of research specialties are connected to the key questions raised by Chubin in his 1976 review of the field "The Conceptualization of Scientific Specialties":

- What are the social and intellectual properties of a specialty?

- How do specialties grow, stabilize, and decline?

- What are the temporal and spatial dimensions of a specialty?

- How do specialties vary in size, scope, and life expectancy?

- What are the institutional arrangements that support specialties?

- What impact does funding have on the kind and volume of research produced in a specialty?

- What kinds of communication relations sustain research activities in a specialty?

- The sociological approach (seems to be much more developed than others): science as an institution (Merton); science as a system of beliefs (Bloor, Barnes, Collins); science as culture (Latour, Woolgar, Knorr-Cetina); science as collaboration and competition (Whitley, Gibbons); science as boundary making and demarcation (Gieryn)

- Bibliographic or bibliometric: relevance (topics, novelty, availability, etc.); citations and co-citations; author co-citations; co-word analysis

- Communicative approach: knowledge diffusion through informal channels and discourses and rhetoric in science

- Cognitive approach: paradigm shift (Kuhn) and branching of ideas (Mulkay)

Mapping research specialties helps to find the structure and dynamics of a research specialty and can include:

- A map of the network of researchers and research teams involved with the specialty.

- A map of the base knowledge supporting research in the specialty.

- A map of current research topics in the specialty.

Others goals of mapping include:

- Mapping the social network of researchers - identify and characterize researchers and teams of researchers and their sponsoring institutions in terms of productivity, impact of research results, weak ties, levels of participation and collaborations.

- Mapping the base knowledge in the specialty - concepts, theories, methods, controversies

- Mapping the topical structure

- Mapping the relations - researchers, concepts, and topics

- Mapping changes - shifts in base knowledge and topics, new subtopics, productive researchers, changes in funding

The conclusion is not very optimistic though:

The problem of mapping specialties is complex and poorly defined. A number of techniques have been developed and applied. Each of these techniques reveals some separate aspect of the specialty. For example, co-authorship analysis uncovers the social structure of collaboration and research teams in the specialty, co-citation analysis uncovers structure of base knowledge in the specialty, and bibliographic coupling analysis reveals research subtopics. In and of themselves, these analytic techniques are inadequate as tools to map the whole research specialty: the social structure of researchers, the base knowledge they use, and the research topics they study. ... the metaphor of the blind men and the elephant is appropriate, as each analytic technique reveals the specialty in some limited aspect.

What is the solution for examining a specialty as a whole? Combine as many existing techniques as possible or develop some new techniques?

No comments:

Post a Comment